THE RELENTLESS CAMP VULGARITY OF KEN RUSSELL

Friday, December 2, 2011 at 06:30PM

Friday, December 2, 2011 at 06:30PM In honor of Ken Russell's passing, here are notes on his style perpared for my cinema studies course "Up Jumped The Devil."

“He raised funds for Tchaikovsky by telling investors it was ‘a love story between a homosexual and a nymphomaniac’.”

David Thomson

Biographical Dictionary of Film

Elements of a Director’s Style: Ken Russell

THE DEVILS (1971)

1) Subject Matter:

The sensual pleasure/terror inherent in just about everything.

How self-destruction grows from ambition, passion, desire, creativity or love.

How love, creativity, passion, desire and ambition fuel self-destruction.

How society undermines the odd, the creative, the independent.

How desire makes women neurotic and men bestial.

Color

Extremes of emotion

History & biography in which facts matter less than drama.

2) Script:

Based on the Aldous Huxley novel The Devils of Loudon, The Devils more or less follows a power struggle between Cardinal Richelieu of France and a roguish priest who serves as governor of the town of Loudon. Richelieu, determined to turn France Catholic by slaughtering anyone who was not, insisted that towns tear down their fortified walls – that towns make themselves more vulnerable. The priest/governor of Loudon refused, but was undone when local nuns accused him of Black Masses, seducing them, etc. The presence of Satan was detected, the Inquisition came to town and bad stuff happened.

Like all Russell scripts, the historical events (the life of Tchaikovsky or Liszt or Mahler or Isadora Duncan) serve as a jumping off point for Russell’s singular ability to exaggerate every human emotion or interaction. You’d think that scenes of nuns masturbating themselves bloody with crucifixes wouldn’t require much exaggeration, but Russell finds a way. Like most of Russell’s scripts, The Devils is too wordy, too self-aware, too full of its own flare. And, like most of his scripts, the story remains compelling. We want to know what’s happening and why, even as we peer through this fog of self-indulgence.

Given Russell’s juvenile penchant for epatier le bourgeois, he should regard The Devils as his triumph. His detailed depiction of Catholic blasphemy got the film banned in Italy. The two stars – Oliver Reed & Vanessa Redgrave – were threatened with arrest should they ever visit that country.

3) Images - Composition and Lighting:

The colors are lurid, the light is too bright and the camera makes bravura moves, which, like all of Russell’s effects, call attention to themselves at the expense of audience involvement in the story. Though Russell understands the grammar of cinema well enough to fuck with it non-stop, it’s as if his eye can’t bear a simple expository shot. Every emotion or narrative point in the frame has to be underlined five times and pointed out to us in neon.

This renders his films hypnotic and exhausting. And leaves an audience feeling messed with as well: sincerity and/or naturalism are not Russell’s modes. That said, Russell knows the power of a close-up and how to structure character through scale and placement within a frame. He’s a good visual storyteller and for better or worse, keeps the narrative – however fractured - moving forward. And, as Pauline Kael said of Godard, Russell turns most viewers into film critics. You can see his technique in front of you constantly, so you start thinking about why he’s doing what he does.

Cinematographer David Watkin shoots The Devils with a combination of late-‘60’s psychedelic expressionism and early ‘30’s Carl Dreyer austerity. His fixed compositions are stately and frightening. His hand-held work, while shooting too close in close-ups and moving all the time, remains unflinching. It’s a beautiful film.

4) Acting Performances:

Over the top and then some. Sometimes. Think of Tina Turner as The Acid Queen in Tommy. Conversely, think of William Hurt and Blair Brown in Altered States. The former is pure camp, like most of Glenda Jackson’s and Oliver Reed’s performances for Russell. The latter are understated, naturalist and true. Understated, that is, by Russell’s standards. If Altered States is Russell’s most conventionally successful picture, then it naturally features his most conventionally successful performances.

Russell has gotten startling work out of stars whom we do not think of as actors, like Richard Chamberlain, and gotten worthy actors to star it up all over the place, like Vanessa Redgrave in The Devils. Russell’s actors are involved. No one goes about his or her job half-assed. Their performances often feature the exaggerated facial exercises of the silent era.

5) Pace, Cadence and Rhythm:

Maddening…Russell will bring the story to a complete halt to indulge in some ludicrous moment that no one cares about save him, or present a scene with such delicate awareness that you want to weep. Mostly, his films lack rhythm or pacing. Scenes lurch into one another, shift season or year without warning, jump-cut across eras or across the dinner table. He knows and understands suspense and how to build it, in his own overly dramatic stylized way. Because The Devils unfolds in one place and in a unified space/time continuum (unlike, say, the life of Tchaikovsky), Russell sustains a pace that seems suitable to the tale.

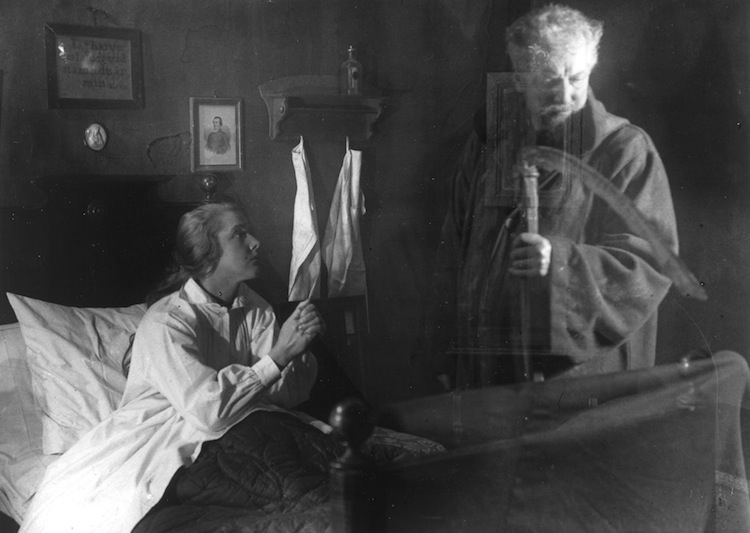

No, that is not Warren Zevon.

No, that is not Warren Zevon.

6) Editing:

Flashy, irritating and very effective. Russell seems to thinks that no one in the audience has ever seen a film before, and will – like primitive tribespeople astonished by mirrors – have their minds blown by cuts to weird close-ups or grand guignol effects that startle nobody. Like his actor’s performances, the redeeming strength of Russell’s cuts is his overwhelming intentionality. He knows he’s going somewhere and wants you to come along. His conventional within-a-scene cutting -from master to two-shot to close-up and back - is often hackneyed and television-like, as if conversation, even those key to the plot, bores him. If the subject is white-hot passion - jealousy, lust, impending depravity - Russell cuts with greater ferocity as the characters interact. If the scene is exposition, he can’t be arsed.

7) Use of supportive elements: design, costumes, music, etc.:

The English punk/madman director Derek Jarman (Jubilee, The Tempest) served as Production Designer and seems to have modeled his sets after Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. He and Russell did not remake the historical period of the tale. They present a combination of futurism, retro and Expressionism. A hedonist, Russell is infatuated with color and texture and revels in the fabrics and brocades of the historical period.. Russell understands the political hierarchy of decoration within the Church, and he shows how power accrues to those permitted, say, to wear purple. The score is, as always, overdone and intrusive. The Devils showcases sets, costumes and interiors as commentary on the story/characters and as characters on their own.